Kene’s sister Ifeoma, often described him as ‘impulsive.’

Kene however had not been hasty over his momentous trip to the part of Nigeria where Bobo resided. He had dithered. His schooldays’ friend, Bobo, who sometimes stayed with him in Abuja, had continually urged him to visit. ‘The pace of life is different in my town,’ Bobo had said. ‘I know nice hangouts. Just come and chill there for some time. My doors are open… oh, what’s wrong?’

On Bobo’s last trip to Abuja with his new wife Mira, the couple had spent a week as Kene’s guests. Mira had added her plea to her husband’s. ‘Our home is there for you. I’ll cook, cook, until you belleful! Just come. Maybe you’ll even find a wife there…’

‘I’ve a girlfriend,’ Kene had reminded her.

‘You go dey for girlfriend die?’ Bobo had chuckled. ‘Anyway, this is not about matchmaking.’

‘You want to “retaliate” my hospitality,’ jested Kene. ‘You don’t have to, you know.’ All three chuckled at the allusion. It was the famous faux pas of some public figure who said ‘retaliate’ when what he meant was ‘reciprocate.’

Suddenly, at a time of global alarm, Kene found he had before him a week that was free of commitments. He boarded a plane to Bobo’s home state. His visit offended rather than gratified Bobo, for Kene checked into a hotel, then phoned the couple to announce his arrival. His action was deliberate. He had reasoned that since Bobo was no longer a bachelor, he should not intrude upon his marital space. He had learnt that having a husband’s friend as a houseguest was irksome to some women.

Kene was also undergoing an inner struggle. It had rumbled fitfully in him for years. His coming to that town strangely expressed both avoidance and embracing of that urge. It was a yearning both adored and abhorred.

He had argued with his girlfriend, Bosede, before travelling. ‘You don’t want to say what you’re going for, suddenly deciding to leave Abuja for a week,’ she had grumbled. ‘Ok, you feel I’m going to see a woman there,’ Kene replied. ‘I know no one there except Bobo and his wife, and I’m not even staying with them. I want time alone, to look into myself.’

She was skeptical. ‘I see. Just be careful… Don’t bring back HIV, I beg you.’ Kene sighed, ‘So suspicious!’

When Bobo and Mira came to the hotel, Mira wept. ‘How could you stay in a hotel and be paying bills when our home is there? We have three empty bedrooms. How have we wronged you?’

‘We know you’re a bachelor,’ Bobo added. ‘Even if you want some woman to visit you in our place, we won’t mind.’

Kene strove to soothe them. They asked him to dinner the following evening, and gave him a lavish feast. He spent the day after roaming the town, preoccupied with his inner prodding. He felt he must embark on it, then decided he needed to attain certain milestones first.

On that day, he heard disquieting news. The Federal Government had ordered that in three days’ time, interstate travel would be banned in the federation. The Covid-19 pandemic had assumed terrifying proportions, and its spread had to be curtailed.

Kene chafed at the forced end to his holiday. He was savouring the town’s peculiarities, and had planned to be there for an entire week. However, he managed to change his travel date, enabling him to fly to Abuja in a couple of days. He could not have known how his stay in that town would be prolonged.

Knowing that the journey to the airport took about 50 minutes in normal traffic, Kene left his hotel two and a half hours before his flight. His taxi coursed along the streets. Less than ten minutes into the easy ride, they encountered a bottleneck. Kene felt panic stir within him, and quelled it. Five minutes later, the vehicle had not advanced, and a long line of cars was behind it.

‘Is there any other route we could take?’ he asked the driver.

‘Yes,’ replied the man, ‘but that one long pass this… but me, I no even fit get out of this now.’

Kene’s heart was thumping. After over an hour, they had not moved even a quarter of a mile. He prayed in desperation, ‘Lord, please don’t let me miss this flight. What will I do… Let the traffic move… Let the plane be delayed. Flights are delayed all the time, and sometimes, cancelled…’

He heard remarks from outside the car. ‘Na trailer crash for road. Person no fit move until they remove the trailer…’ Oh Lord, Kene thought, it’s a routine process to remove a crashed vehicle from the road. In other countries, trailers don’t even ply in daytime…

It was 12.30, the scheduled departure time of the plane, before normal traffic was restored. ‘Speed, faster, faster…’ he panted repeatedly at the driver. They duly reached the long driveway to the airport, and the driver raced towards the departure building. Just before they reached it, they heard the roar of a departing aeroplane. Kene did not need the information shortly imparted: ‘The plane done go. The last before lockdown.’

He simply had to remain in Bobo’s home state for an interminable period, or travel to Abuja by road. Kene had never considered taking that road trip. It would be at least 10 hours on highways, long stretches of which were badly damaged.

Kene boarded a taxi back to town. He could not afford to stay at the hotel indefinitely. He now espoused an option he had repulsed, and called Bobo.

‘Come here now,’ Bobo roared. ‘Your room is waiting.’

Kene was cheered, directing the taxi to Bobo’s apartment. He phoned his parents in Lagos, lying to spare them anxiety. ‘I’m back in Abuja. I’m fine… can’t travel now, of course. Please be careful. No visitors.’

The next morning, feeling he must at least have substantial cash on him, he sought an ATM.

On that day, he cursed and cringed. The crowd outside the bank surprised him. Although only a few people at a time could now be allowed into banking halls, he had not expected the lockdown to breed such scenarios. He slid his card into the machine, and it was trapped. Kene sought to enter the bank and report his plight. The surging throng made it impossible. He stood and strode about in the scorching sun, while some hardy people jostled their way inside. After a few hours, the bank was shut for the day.

The following day was a Saturday, and the bank would not open until Monday. He could not leave Bobo’s place before that day.

Back at Bobo’s and Mira’s, he reported the situation to his friend. By the following day, his status in the apartment had dropped. Mira was dour and listless as she served him a meal of garri and vegetable soup.

The weekend dragged on. Mira became increasingly hostile. She came upon him watching a television programme in the sitting room. ‘No, not that channel,’ she snapped, instantly switching to another channel. For breakfast the following morning, she served him a bowl of corn pap. Kene recalled that she had given him sliced bread with margarine and a boiled egg the previous morning. He looked around, and failing to find sugar on the table, asked for some. ‘You can drink it with salt,’ Mira said. Kene suppressed his anger. Corn pap was sour, and sugar mitigated its faint tartness. Salt would only exacerbate it. Not even in boarding school days, when deficient feeding was routine, had Kene seen pap drunk with salt. He silently bemoaned his neediness. In the hotel, he had at least obtained cornflakes or toast and omelette for breakfast, but he could no longer afford to return there…

For the rest of the weekend, he kept to his room, emerging only to eat meals dispensed with bad grace by Mira, or to take long walks.

Early on Monday morning, without eating breakfast, Kene undertook the two mile walk to the bank. He was dismayed to find there was already a crowd outside. Trickery was manifest. ‘People have been here since 5 am,’ he was told. ‘You have to write your name and get a number.’

Fraught minutes passed before he could put his name on the list, obtaining a card with a number. Even before then, he saw that the process was futile. The queue was being continually violated, and people were being smuggled into the bank. The numbered cards were being sold by some who had come early, only to secure cards and sell to others. Kene had neither the cash to bribe, nor the ruffianism to elbow his way through.

Sometime between 1 pm and 2 pm, it was announced that there would be no more entries into the building.

Crestfallen, he trudged back to the house. He could not ask any friend in Abuja to transfer money to his account, as he could not access his account. He knew no one in that part of the country, except Bobo and his wife.

‘How did it go?’ Mira asked him. ‘Terrible,’ Kene answered. ‘I couldn’t even get into the bank.’

‘Hei,’ exclaimed Mira, ‘for how long could we carry this load?’ Kene contained his fury. Famished and feverish, he was not too proud to ask for food.

Mira served him garri and egusi soup devoid of meat or fish. Kene had seen her finishing her meal, chunks of meat in it. To assuage his hunger, he ate what he was given.

Later, he lay brooding in the room assigned to him. He had never been so directly confronted with the reality of penury. He smiled as he recalled a verse in the Bible’s Book of Proverbs: ‘money answers to everything.’ The same Book, he knew, also counseled, ‘do not toil to acquire wealth, be wise enough to desist…’

Kene was desolate. For the first time in years, tears stood in his eyes. The following morning, he rose at 5am to go to the bank. There was already a small crowd there, but he was able to gain entry. He made a startling discovery. ‘Sir, your account is under PND… A PND means “Post no Debit.” There might have been an STR…’ Kene panted in anguish, ‘what’s STR?’ He was told, ‘It’s “Suspicious Transactions Report…” perhaps there were suspicious withdrawals… taking out more than you should… It also happens sometimes when some documents were overlooked when you opened your account… there are four valid IDs we can use…’

Kene staggered out of the bank. He was now faced with the humiliation of asking Bobo for a loan.

He sought Bobo alone, explained his plight and made his request. Later, Mira strode into Kene’s room to rage: ‘this your asking my husband for money… where do you want him to get it from? One mudu of garri now costs one thousand five hundred; it used to cost five hundred… salt is a problem… this is Corona time. New yams will not be in the market for another three months. Already, we’re feeding you. We’re tired o!’

Kene did what had become his habit: quietly swallowed his bile. He was respected, even lionized, in social and professional circles in Abuja. He had after all hosted Bobo and Mira sumptuously in Abuja… Well, he told himself. It’s an experience. I’m learning.

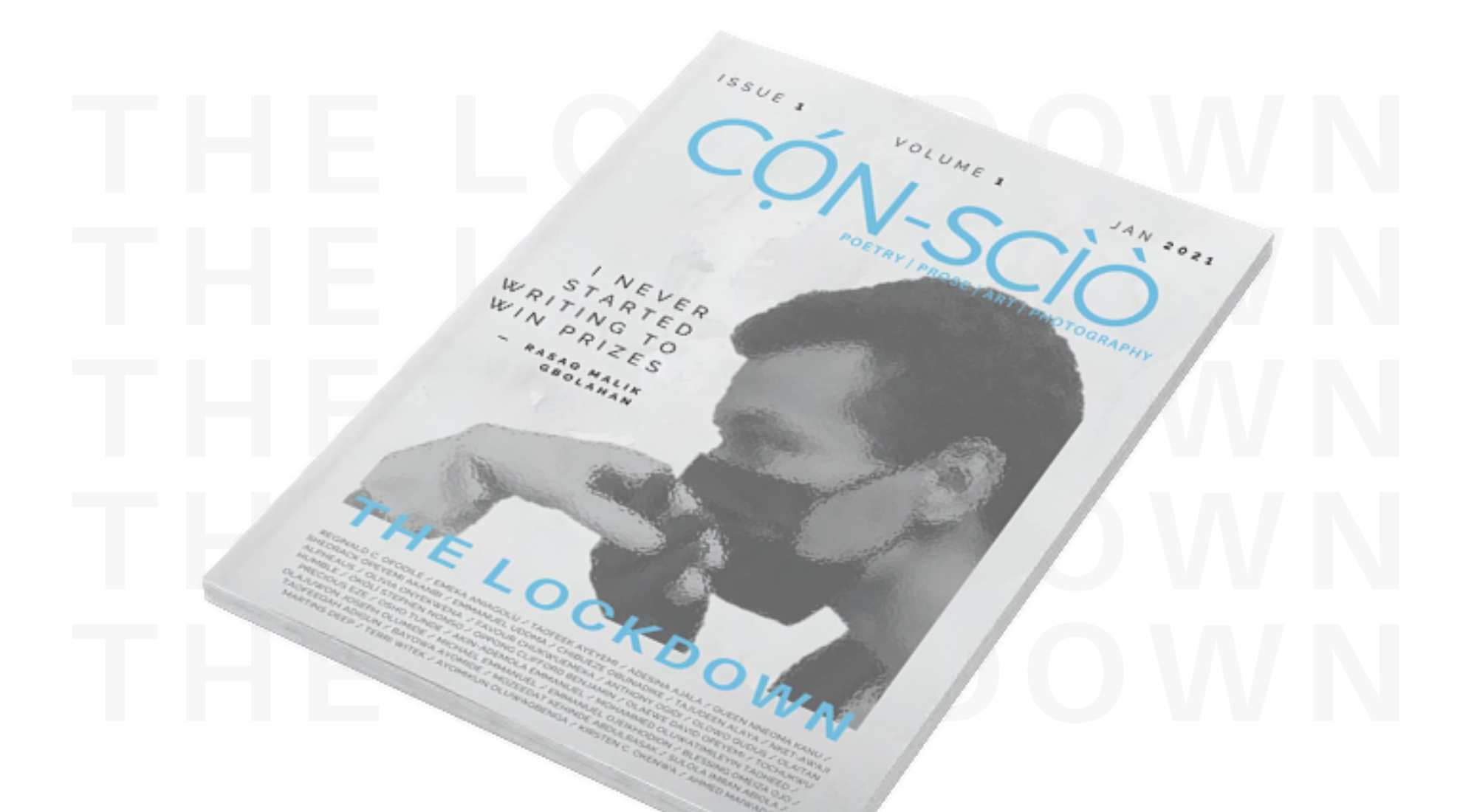

Strangely, the urge with which he had long tussled – the yearning to engage in creative writing – overcame him. Kene had dismissed it as fey or escapist. He had reasoned that it was irresponsible to be absorbed in fantasies whilst one’s contemporaries strove for money and comforts. At other times, he had felt writers were both warped and special. Now he pulled out a sheaf of papers and a pen his briefcase, and leapt into the realm irradiated by Soyinka and Achebe. In his deprivation and desolation, his subconscious summoned sumptuousness and sanguineness…

It was an event which Nigerian society would remember for decades. The ceremony was customary and commonplace: a traditional betrothal/wedding (the ‘trad’ wedding), also designated ‘wine-carrying’ because it was the formal presentation of palm-wine and bride price by the groom and his family to the bride’s father. However, the lavishness of this particular ceremony was stupefying. There were numberless marquees stretching farther than the eyes could see, air-conditioned, with carpeted floors, and other luxurious furnishings. The spread of food in the marquees was astounding. On long white-draped tables, attended by chefs in towering toques, were laid grilled whole fishes. These ranged from the choicest piscine item, asa, to large white fishes from the waters of Port-Harcourt. There was an assortment of salads, gigantic tureens of steaming soups, with huge cutlets of fish (both fresh and smoked), chunks of goat-meat, beefsteak and oxtail. There were platters of flush jollof rice, fried rice with shrimps, and white rice with orange-coloured stews and beige-coloured sauces. There were vast arrays of roast chicken and dark-fried cuts of other meats, spreads of roast potatoes and macaroni, breadfruit dishes, and balls of pounded yam and semolina. There were puddings galore, confections ranging from strawberry sandwich cakes with cream, to egg caramel which exuded tantalizing aromas of burnt sugar. The offerings impelled unabashed gluttony.

Each marquee boasted an unlimited array of choice and chilled beverages – vintage champagne and other costly wines, as well as superb cognacs and whiskeys, beers and soft drinks. Band groups were about, giving renditions of romantic ballads or upbeat music.

Everyone suddenly focused on the main sitting room in the mansion. The assemblage of grandees was hushed. The climactic moment had arrived. The bride, clad in a riveting wrapper embroidered with gold and silver thread, rhinestones and pearls, her spectacular coiffure featuring corals, gold and diamonds, accepted a cup of palm wine from her father. She was expected to find the groom from among the men present, offer him her the cup of wine, then lead him to her father. She duly found her groom. Their eyes met. Time was suspended. In their enchantment, their unspoken words were, ‘if our trad wedding is so grand, how will our church wedding be…’

The bride of Kene’s vision was strikingly like his girlfriend, Bosede, with her glowing skin, straight nose, alluring eyes and lips and superb figure. The phone’s sudden ringing proved his spirit had conjured Bosede, for she was the caller!

‘How is it going?’ she asked, sounding forlorn for she was aware of his predicament. Kene mustered elation, cooing, ‘I’m ok, baby. Ok as can be.’ Bosede became mistrustful, dropping her initial concern. ‘What are you doing?’ she asked.

‘You don’t want to know, Baby.’

‘Well,’ she concluded. ‘I’m glad you’re at least cheerful.’ He duly told her his problems were not solved, but he was certain to overcome them.

On that night of his venture into letters, Kene was suddenly impelled into an act he had long abandoned. He knelt to pray for divine help. Afterwards, he felt disburdened.

The next morning, dressed in a suit, he returned to the bank. He was saying silent prayers. After only a few minutes’ wait, he was able to bluff and shove his way into the banking hall. Haughty, speaking upper-class English, he demanded to see the manager, presenting his card. The staff attending to him hesitated, then reluctantly showed him into the manager’s office, where Kene explained his plight.

Kene saw a miracle unfold. ‘We can’t be that strict in these times… People have to survive. How could a man of your class be stuck in another state for heaven knows how long, without cash to get by?’ the manager said. He authorized a withdrawal from Kene’s account.

Kene left the bank with a bulging wallet. He heard the conversations outside the bank. ‘You think lockdown na total lockdown? No be Naija we dey? Who dey keep law here? People go travel despite lockdown. Just go to motor park, dem dey load for Lagos, Abuja, Benin… everywhere.’

Jaunty, Kene stopped at a shop to buy Mira a bottle of perfume. On reaching her home, he presented it with gleeful gallantry. ‘Thank you for being a longsuffering hostess. I’m leaving today.’

Mira evinced concern. ‘How could you go? With this lockdown… I hear drivers go into the bush to get from state to state… dangers… attacks… Boko Haram and kidnappers… it’s like going to die.’ Firm in his faith, Kene replied, ‘I’ll get to Abuja without sustaining a scratch.’ He thought, I’ve much to thank her for. Being in her house has driven me into myself, and made me take up the creative writing I’d long avoided.

Bobo drove him to the motor park to board the evening transport. Kene was intrigued by the novelty: he had never undertaken an overnight road journey in Nigeria. He was shortly installed in the Sienna saloon car, for a trip which promised to be long, arduous, and hazardous.

Kene slumbered fitfully. They traversed roads even or pothole-riddled, jerked frequently by the car’s motions. As day broke, he heard the driver remark that they were about two hours to Lokoja, which was about two hours to Abuja. A long, wooden pole, studded with long nails sticking out like spikes, was flung across the road. The driver screeched to a halt. Doors were thrown open, passengers wrenched out. Guns were shoved in passengers’ faces. Orders were barked for monies and jewellery to be forfeited. The terrified passengers complied. After the operation, they were allowed to resume their journey.

The fright remained. Kene and the other passengers continued to tremble in their seats. Kene’s terror was reflected in his damp and reeking trousers. They did not know that further torment awaited them. Deafening gunfire blasted their eardrums and an invisible vehicle swerved into the road. Hoodlums sprang out, throwing open the Sienna’s doors, battering and tying up passengers, demanding 50 million Naira ransoms for each. The travelers were traumatized into delirium…

‘Oga, please. It’s enough… Wake up, abeg, you’re disturbing us.’ Angry voices penetrated Kene’s consciousness. He attained full wakefulness, and the car was still on its swift and unhindered course to Abuja. His tremors continued long after he realized that he had only been dreaming. As though to make his nightmare real, a roadblock suddenly loomed. It was manned by uniformed men who rasped at the driver, ‘where you dey go? You no know say lockdown dey? Na you people dey spread Corona and kill person.’

The driver was calm. He slipped some notes into the palm of one of the men. The bribee looked at the cash, removed the roadblock, and the car resumed its journey.

GLOSSARY belleful repletion/a full belly mudu measure of rice, garri and beans garri grainy food made into edible mash Oga boss/master (term of respect for a male) Abeg please/I beg

Reginald Chiedu Ofodile is an award-winning author and international actor. Ofodile has been a very prolific and versatile writer, producing three novels, two books of plays, two poetry collections and a collection of short fiction, as well as essays and criticism. His awards include the Warehouse Theatre International Award in 1997, the BBC African Performance Award, the World Students’ Drama Trust’s Awards and the 2015 ANA/Abubakar Gimba award for a short story collection. He has also appeared across nations on stage and screen in many productions and coached actors.