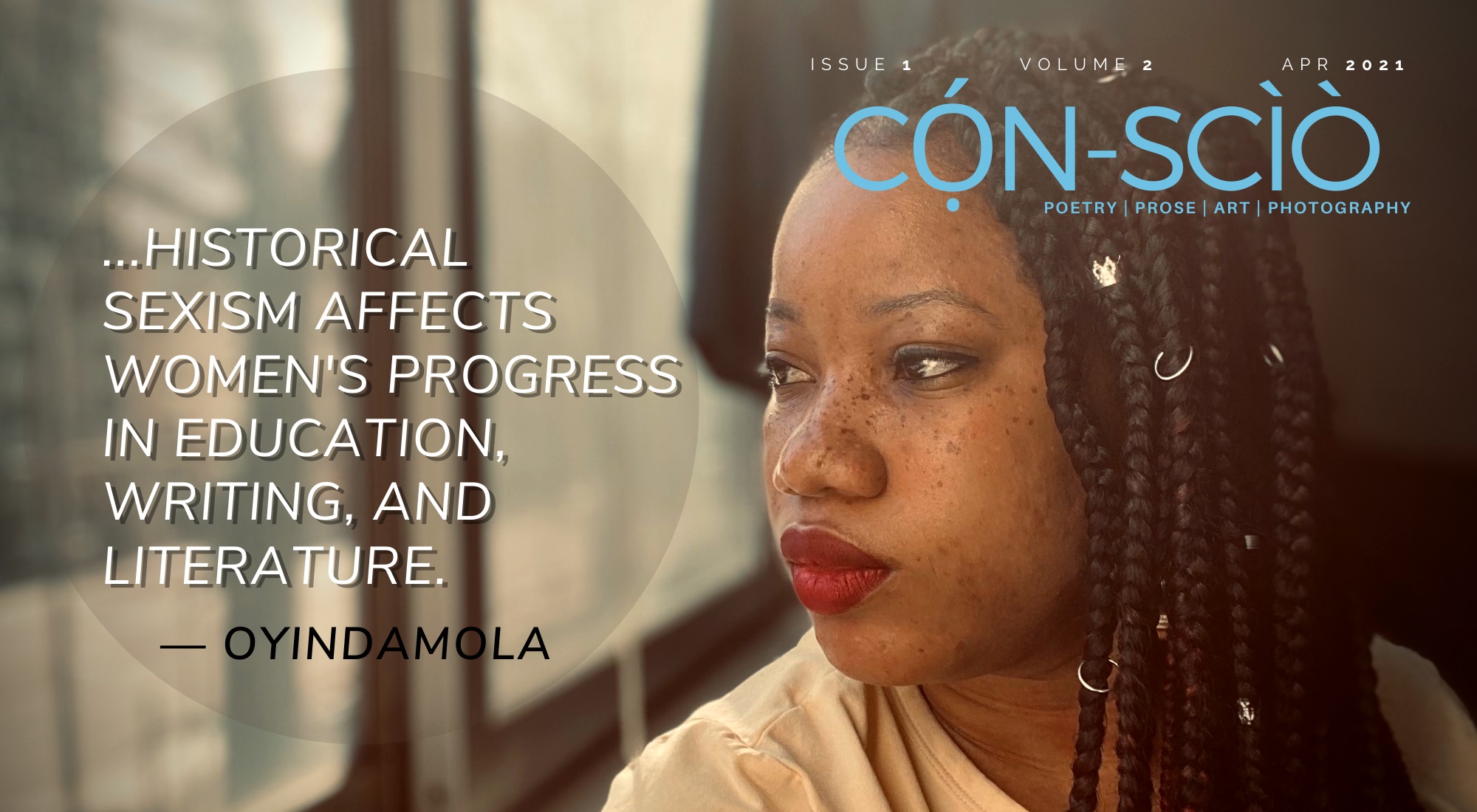

Oyindamola Shoola is an author and the Co-founder of SprinNG – a non-profit dedicated to supporting developing Nigerian Writers. Some of her published books include To Bee A Honey, The Silence We Eat, and Now, I Want to Remember. Oyindamola graduated with many honors from New York University in 2020 and a bachelor’s degree in Organizational Behaviour and Change. In this interview with CỌ́N-SCÌÒ MAGAZINE’s features editor Ehi-kowochio Ogwiji, she talks about her writing and the place of women in the Nigerian literary scene.

As a writer, you belong to several writing constituencies – black, young, female, Nigerian, African, diaspora, feminist, etc. – depending on the circumstances. All of these identities are important in our increasingly polarised society. Do any of these identities affect you(r writing)? If yes, how do you manage them?

OYINDAMOLA: Yes, my identities affect my writing but not all at once.

I shared with a friend recently that I realize how I live “my writing life” in the phases of which identity is most significant. For example, when I wrote To Bee a Honey, I was an ardent feminist. Now, not so much. These days, the things I find myself writing are funny poems in the voice of a sarcastic Nigerian and @HalimaSeries, who I represent. My Nigerian identity has always been important to me. However, it became even more relevant in the past months with the #EndSARS protests. Not to say that I will write specifically about the #EndSARS event, but it increased the consciousness of my Nigerian identity.

My phases surprise me with what they bring, and I hardly find myself writing about all these identities at once. Sometimes, I realize the identity I experienced after the phase has passed and the chap(book) is complete. It took me a while to come to terms with my growth pattern as a writer, which is something I’ll recommend every writer does. There is this ancient Greek aphorism about knowing oneself, which speaks well to this issue – “To know thyself is the beginning of wisdom.” As young or developing writers, we spend so much time studying those we admire that we forget to study ourselves and understand how our identities affect our writing or growth pattern.

Speaking of constituencies, you said in an episode of Women Who Inspire at Feminine Collective that women need “the courage to use the voice” they have and not necessarily to ‘find the voice’ because they already have it. Bringing this to the Nigerian context, why do you think we have fewer (known) female writers, even among the upcoming ones? What tips would you give women seeking the courage to use their voice?

OYINDAMOLA: One of the crucial reasons we have fewer known female writers is because the conversation of “why” hasn’t changed. Every time I come across commentaries about this topic online, the common conclusion people choose is that women aren’t doing enough or putting themselves out there. While that reason can be valid, I think we have used it for too long and it didn’t change anything, so maybe that’s not the only or right reason we should be looking at.

We don’t have a system in place that automatically, easily, or with the necessary support places female writers at the forefront of writing opportunities the same way it could happen for male writers. For example, statistically, and you can find these numbers on several websites – the literacy ratio in Nigeria for men and women is unequal. Same as the access to education.

In Nigeria, we don’t talk about how historical sexism affects women’s progress in education, writing, and literature. We talk about how colonialism has affected the country or set it back from other nations, but when it comes to women in the publishing industry, we often expect that they will be at the same level as men, and if they aren’t, then it is their fault.

Relocating and schooling abroad, I have seen how systems, programs, and opportunities have been put in recognition of the way slavery, sexism, and other discriminations have affected marginalized groups. So, instead of merely concluding that people within certain marginalized groups are, for example, not passing SAT exams because they aren’t trying enough, I have observed how organizations and schools reflect on ever-current historical effects. Then, they establish opportunities and resources to give individuals of these underprivileged groups the bump they need to try effectively at the same level as individuals from privileged groups. It may not solve all the problems, but it provides a different type of progress.

And this is just one of many perspectives and reasons. This isn’t to say that view should be the only way we talk about women’s representation in this industry. I also realize, especially with the work SprinNG does, that there aren’t fewer female Nigerian writers as it is often concluded, even among the developing ones. If one takes the tremendous and intentional effort to search them, you will find them. But that’s a conversation for another day.

About tips for “women seeking the courage to use their voice.” Maybe I’d have jumped to advising in the past, but these days I murmur the response, “What does that question even mean?” While it may come off as a sarcastic answer, these days, I am finding it to be the right answer, at least to myself. I see this question in many interviews, even for other authors, and I feel for women who read these suggestions, bombarded with advice that may or may not apply to them. So, because we have different causes of fear, my response to those women is, “What does it even mean to lack the courage to use my voice?” When you find out

Your non-profit organisation, SprinNG, has done a lot for Nigerian writers through several impressive initiatives and recently created the annual Women Authors Prize to promote female writers. Why do we need this prize? How do you fund it? Are you satisfied with the results so far?

OYINDAMOLA: Following my response to the previous question – we need this prize because it starts a different conversation about why there are fewer known female Nigerian writers. It also importantly shifts the conversation from blaming women for a possible societal failure in their representation and us, being an example for those who choose to take responsibility in changing this failure. The more challenging question for any progress in our society is always, “what can I do about it?” I often find that people don’t ask that question because it requires them to act, get uncomfortable, and work to change.

Not to say every literary organization should start a women’s prize, although that will be nice; in your work, do it with the consciousness to uplift voices that have been historically put to the back. And don’t just try it out once, then give up on your contribution for change. You’ll realize that it will take years to undo the damage created, established, and institutionalized for centuries.

On funding the prize, last year, we started with a base amount of N100,000 and doubled it with the support of a sponsor. This year, we haven’t made any conclusions about what the prize’s funding will look like, and we’ll keep all our followers updated as soon as things are finalized.

The prize is only less than a year, so I don’t think I am at that point where I am focused on my satisfaction with the outcomes. Right now, I am just concerned that something is being done beyond my past social media rant about this issue. I also don’t want to aspire for personal satisfaction on this prize. Not to conclude that I am, but I am very alright with being dissatisfied every year in a way that makes me and the SprinNG team want to do better or more.

Are we happy that we started this prize at all? Yes! Are we surprised about the social media following and attention it gained in such a small amount of time? Absolutely.

You are quite a prolific writer. You authored almost half a dozen books and chapbooks in under a decade. How did an “indecisive writer” (as you called yourself) achieve this?

OYINDAMOLA: Haha! Recently, while I was doing some self-hype, I said to myself, “I think I am a badass writer because I am indecisive and can write almost anything.” Like I wrote in my response to the first question, the knowledge that my writing is based on my life’s phases makes it easy for me to write progressively. I have a different level of confidence about my writing, knowing that as long as I live and have new experiences, whether daily or in phases, there will always be something to write about.

I publish frequently and perhaps have that many books because I write to let go of these phases. It is also an experiment towards my larger book publishing goals. It is my way of trying new things and finding out what is working or not while establishing my audience.

My indecisiveness has also been a poison in that it has caused instability in my relationship with my audiences. You see how writers can be poets and poets alone… I can’t be just one thing. You’ll find writers who can devout all their life to feminism or another prominent theme; that’s not me. I get bored often, and I change my mind too much. I am continually learning to wake up and confidently change my mind when I feel like it, whether my audience moves with me or not.

Three of your most successful books – To Bee A Honey, The Silence We Eat, and Now, I Want to Remember – dwell heavily on the themes of feminism and womanhood. Why are these themes important to you?

OYINDAMOLA: I think the need for the world to do better on women’s issues like inequality, sexism, and violence, is undeniable, and that’s why these themes are important to me. I am a woman, and the shared experiences that come with womanhood are also important to me, which is why I write.

However, I think I have grown out of that space, whereby that’s all or what I want to write or talk about. Recently, in several unpublished items – mostly rants on private platforms that a few of my friends and writers in my network can see, I have been a critic of feminism and some of its modern ideologies.

Sometimes, I think because someone else has already said what I’d likely say or written about it, I don’t feel like talking anymore on these topics publicly. The yearning to publish them or have more extensive conversations isn’t there as much because now, I just want to act for change wherever I get the chance to.

Why do you think people are reluctant to call themselves feminists? In your interview with John Michael Antonio, you said, “People are reluctant to call themselves feminist because the title carries so much baggage and the ideas that feminism portrays have become more complicated and unclear,” but you brandish the title so well. Do you ever feel a need to add an adjective that filters off the baggage associated with describing yourself as a feminist?

OYINDAMOLA: I read that statement and can’t believe I said that. Sheesh! You dig too well in coming up with these questions.

On adding an adjective – I think part of the first time I came across the idea of feminism was with Chimamanda’s words describing herself as a “happy feminist” because of a similar reason. Someone had said to her, “Feminists are women who are unhappy,” so she added the adjective.

I don’t think I need to add an adjective in describing my feminism to filter off the baggage. I am a feminist, and I can do my best to present myself as a woman who cares about the progress of all women in all aspects of society. How anyone else interprets it or paints a picture of me from that title is their problem. And I think another person must have a lot of personal baggage to offload it on my identity simply because I am a feminist – it reflects worse on them than it does on me.

Notably, part of feminism is not to be people-pleasing. I see people add adjectives to make others feel comfortable about their feminism and, sometimes unconsciously, the sexism around them. Especially, observing how sexism has been dished out to people with better branding and even adjectives that make it seem not so obvious, it doesn’t sit well with me to filter off my feminism or its baggage. It comes with baggage which I have decided isn’t mine.

In a recent interview, you talked about being afraid of posting excerpts of your book To Bee a Honey because you were “too honest about the experiences that many women face” in the book. This is a valid fear for many writers. How can writers, not just the female ones, overcome this fear and put their works out?

OYINDAMOLA: You know this idiomatic expression “to be in someone else’s shoes” – I think that sums up my style of feminist writing. I don’t know how to sweet-talk or sugar-coat the horrible daily experiences women have due to sexism. Even more recently than the statement you quote in this question, I experienced a worse backlash for a nonfiction piece I wrote about sexual assault, particularly rape. Despite my note of caution at the beginning of the piece, I was so heavily criticized by even people who only read the title.

It forced me to the harsh realization that sometimes, some people only want to talk about women’s issues like rape when they can choose to be oblivious about what the experience is like. They only want to talk about what I identify as “convenient feminism.” Women are made to feel uncomfortable by so many things happening in our world, and that, to me, is the conversation of my feminist writing. I often ask these people who feel uncomfortable from reading… Do they know how uncomfortable many women feel from experiencing such sexism every day? Do they know how many women feel about living in a world that condones a violation of who they are because of their gender? I don’t think I am at that place where I can or want to advise anyone who has a fear associated with putting their works out for any reason. These days, I would rather just listen and say I understand. I am still figuring it out – navigating the fear of putting my works out there because I don’t know how to write dishonestly or sugar-coat my ideas. While I could recommend ways for a writer to twist and turn their works or even themselves to overcome this fear or live in a society that makes them feel afraid, I am at that space whereby I think to myself – what if their anxiety is valid? What if it is something else in their society that needs to change so they won’t be too afraid?

In a piece, you wrote for Black Fox Lit. Magazine, you listed ‘silly poetry’ and ‘less poetic poetry’ as types of poems you see from Nigerian writers and went on to call some of them ‘a bunch of misplaced words fitted as puzzles on a sheet of paper.’ What do you mean by these terms, especially ‘less poetic poetry’? Do they have any link to recent conversations about the changing (and largely prosaic) nature of ‘modern’ poetry?

OYINDAMOLA: My more-updated thought on this issue is first, I understand that these types of poems are perhaps written for personal expressions rather than academic or literary purposes. Second, I can see how these types of poems may be a better introduction to the world of writing or poetry-reading. Third, there is clearly a growing audience for these types of poetry which makes their existence valid and recognition, arguable.

However, I think standards need to be set and followed to help demarcate what’s poetry or not. Let’s even use the basic definition by Wikipedia as a guide, “Poetry is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language—such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre—to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, the prosaic ostensible meaning.”

So, when I see people write a sentence or what should be a quote and call it poetry, I think, if quotes are poetry, then all the famous people who spew cute words are on golden globe podiums that are eventually quoted into motivational pictures should be called poets. Poetry can be about feelings, but that isn’t all it is about. If it is only feelings required to be a poet, then babies will be the best ones. If I can’t write a poem and call it an essay, why should I write an essay and call it a poem? I know the lines aren’t all black and white, but I often ask, “is this “modern poetry,” or is this just not poetry at all?” Are we forced to call it poetry because many people are doing it that way or because it truly follows the precedence of what poetry should be? I ask these questions a lot and have relieved myself from forcefully accepting what’s not poetry on certain standards to me, based on historical and academic learnings.

While I no longer view these poems discriminatorily, primarily because I serve as a judge in some writing contests, I have questions when I come across these poems. Like I wonder about the random spaces in between words or use of the small letter “I” or the unnecessary excessive use of slashes “/.” I just sit there and wonder, what effects did the poet think this would communicate to me? Are these meaningful or functional to the overall poem? I ask these questions because reading historical poets who used similar styles… they had meaning and function – such that there was a feeling of enthusiasm to decipher or find them; and a feeling of joy or “aha” when found. I have also stopped providing editorial support for poetry because of these reasons. When I read a poem written like that and the author’s intention aren’t clear, I don’t know if the lack of a comma or an intrusive use of another punctuation was intentional from the writer as a part of their style or a typographical error.

I don’t get to decide what poetry is and is not. No one is also bound to agree with my perspective of what poetry is or not.

I even critique my works based on this reasoning and have found some failings. But I think the problem with making just anything poetry is that people can now believe everything written is poetry. And poetry isn’t just anything or everything. However, I think it is a necessary and on-going conversation in our literary communities and among our writers.

I will not say that an academic or educative foundation in poetry writing is mandatory for one to be a successful poet; however, I question its lack, especially in this new wave where people want writing to be a serious job or career. Other times, I question it when I read these poems, and although they are deeply personal and meaningful to the writers, I honestly just don’t understand or enjoy them.

Finally, I think we should stop this lousy advice we give to writers about “breaking all the rules” when writing. I often wonder, if you don’t even know the rules, then what exactly do you think you are breaking or attempting to create as a form of rebellion?

“A bestselling author (I hope!)” is what you told We Rulethat you would like to be in 10 years. Now, can you share the steps you are taking towards achieving this target so that other writers may take a cue from you?

OYINDAMOLA: Well, I think there is no one way or path to become a bestselling author.

What I have done in the past five years is first, build my brand. Second, I have gained several book-publishing professional experiences like internships. So far, I have interned for Hachette Book Group, a division of the third-largest trade and educational book publisher in the world. I have also interned for Simon and Schuster – a top trade publishing company. Recently, I interned for Elsevier, which is a science, technology, and academic book publisher. I got outside my writer and reader hat with these internships to see what publishers and editors are looking for when acquiring authors. It was also a learning experience to know how they work with authors to become best sellers.

I plan to pursue a master’s degree in Creative Writing hopefully in a year or two. For me, the path to becoming a bestselling author isn’t just about writing, writing, writing. It is also about reading, working, networking, gaining other skills to enhance my writing.

What self-publishing and releasing chapbooks has done for me so far is identifying and building an audience for my work. It has also allowed me to manage (not lower) my expectations about the writer/author’s experience when it comes to book publishing and define book-publishing success personally. Lastly, it provided credibility in some way.

.

You once said purchasing books “felt like a worthy investment.” You will agree that this is not a very common sentiment these days. How do you think we can bring young Nigerians to the point where they can see buying books as a worthy investment?

OYINDAMOLA: I want to say that I am so happy I still feel the same way as I did when I gave these comments years ago. I realize that buying books as a worthy investment is more than buying books.

First, we need to learn not to be pretentious about the books we read, like, and why we read books. Life is too short or long to be reading books you don’t genuinely enjoy. Even in high school, I remember not genuinely loving or enjoying many books I read. The worst part is how you had to analyze or comment about such books as though it didn’t take an arm and leg to get through the first few pages. When you find a book that makes you laugh, cry, feel like you understand something, surprises you, makes you yearn, question, or learn, it is a worthy investment.

Second, not to say books must become cheap, I think books need to become more affordable to the audiences who need them. While I understand that knowledge is invaluable and the pain or hard work of a writer should be compensated, I also think books are sometimes worthless when the people who need it the most can’t even afford it. And this isn’t to throw any shade to authors who price their book very highly because profit is important. However, when your demographic includes people from low-income backgrounds or students, and your book costs N7,500 minus delivery, then there are misplaced priorities.

Notably, I think Nigeria needs to do better in promoting its authors, and I am not talking about the already famous ones.

Every year, when a list of writing awards comes out, it is still the same people you’ll find on that list repeatedly, even if they no longer fit into the category. Like, awarding people who are much older in a “young writers award” because someone failed to research. We now have platforms like WRR, SprinNG, Nigerian NewsDirect Poetry Column and several others, so I think there should be fewer excuses in giving these writers the platforms, representation, or acknowledgment they deserve. Importantly, writers shouldn’t need to move abroad or pursue international success before being recognized at home, especially when it won’t cost them so much to be given their flowers at home. But that’s a different conversation entirely. When we recognize our writers with the intention of diversity, we latently promote their works and a book-reading culture.

I am emphasizing that when people see books by individuals they can relate to with a perspective of representation, they feel excited about purchasing books. So, the country, literary societies, and publishers in Nigeria must do better to expand the model of writers and authors in Nigeria.

.

What are you currently working on? Should we be expecting another book soon?

OYINDAMOLA: Remember, I am an indecisive writer. I don’t know. I never really know when I am writing something worthy of being called “a book.” But I am in one phase now, and I am writing – that is what matters. We will see what comes out of it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.