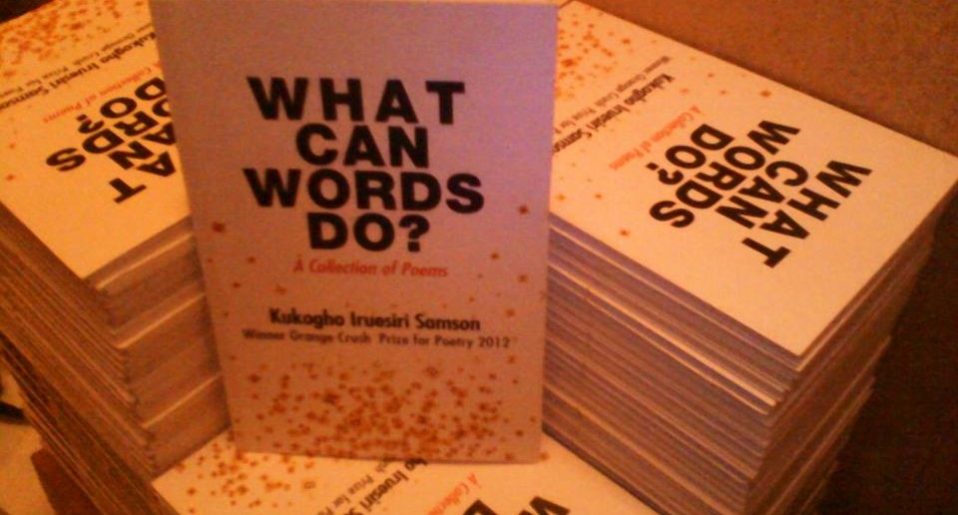

TITLE: What Can Words Do? AUTHOR: Kukogho Iruesiri Samson PUBLISHER: Origami Books (Parresia Publishers), Lagos GENRE: Poetry PAGES: 84 ISBN: 978-1508514794 REVIEWER: Prof. Gbenga Ibileye

Long before the descent into anarchy which the war of the West against terrorism in the Middle East, and especially the Iraqi War of the 1990s signalled, poetry and poets had always been actively engaged in the war of conscience which spoke courageously to power where even mighty men feared to raise their sword.

In this tradition of poetic and literary activism was Yeast who had as a Senator in the legislature of the Republic of Ireland rejected the aestheticism of “art for art’s sake,” declaring, “Literature must be the expression of conviction, and be the garment of noble emotion, and not an end in itself.

“Similarly, Auden’s poem—an elegy for Yeats—concludes by exhorting the poet to “follow right”:

With the farming of a verse

Make a vineyard of the curse,

Sing of human unsuccess

In a rapture of distress;

In the deserts of the heart

Let the healing fountain start,

In the prison of his days

Teach the free man how to praise.

Auden argues further that “In so far as poetry, or any other of the arts, can be said to have an ulterior purpose, it is, by telling the truth, to disenchant and disintoxicate.”

Denis Brutus, the South African poet, used his poetry to fearlessly protest against the apartheid regime in South Africa in his collection, Sirens, Knuckles and Boots, which was published in Nigeria.

Nigeria’s Wole Soyinka has also been vociferous in challenging the excesses of power and the deliberate subjugation of the people through obnoxious public policies and actions in Nigerian society. Much of his writing has been concerned with universal issues which he expresses as ‘the oppressive boot and the irrelevance of the colour of the foot that wears it’.

Similarly, Kofi Awoonor’s Rediscovery and Other Poems (1964), Night of My Blood (1971), and several others of his works and works by his contemporaries in the African continent explore sundry issues which pitch them against the establishment because of the themes which their poetry explores.

This is as against critics who would argue that poetry should not have a voice in (re)shaping society, in the garb of Romanticism which would prefer an undignified, even inelegant aloofness in the name of lyrical fascination and aesthetic preoccupation; aestheticism without a cause and commitment to the ever-present decadence of the society.

Since the Iraqi war, and especially since the creation of the ‘Poets Against the War Movement’, poetry has assumed a sharper and clearer cadence in its relevance and instrumentality in reshaping the political space often fouled by the smelly anuses of political and elite pretenders oozing out farts of discord, hate, terror, corruption and sundry other ails of the modern world.

Can the poet, in the face of such great imbalances and distortions remain aloof, unconcerned by the railroads of power?

Should a poet, especially in our kind of clime where we seem to be cursed with an eternal inability to surmount the hurdles placed on our paths by the burden of clueless men who have foisted mediocrity on us as an emblem of subjugation, remain unconcerned about what happens around him? Can a poet or his poetry not strike a balance between aesthetic elegance and active political engagement?

Should the poetry of an environment so messed up by mad men like ours, no matter its subtlety and veiled pretentions, not reflect the decadence and maleficence of the polluted environment of its writing?

Whether philosophical, cupid, psychological or plain romantic poetry, should we not see snaps of anguish and rays of hope in poems steeped in the forlorn valleys of dashed destinies that our existence as a nation has become? It is yes to all.

It is from the broad purviews of these questions and many more related ones that we can appreciate What Can Words Do?, the latest poetry collection by Kukogho Iruesiri Samson.

The collection which has sixty-one poems covering themes as diverse and profound as politics, environmental degradation, betrayal, poverty, love, religion, family as well as the festering and multifarious crises rocking the Nigerian nation, announces the poet as one who is mindful of the place of Kukogho as an advocate, judge, fighter and educator.

The themes of the poems point to the transformative journey of the poet from childhood through adulthood and the attainment of the resolution of the crises foisted on society by blind men who lead the people.

The title of the collection, What Can Words Do, is a veiled announcement of the poet’s commitment to his poetry and a conviction that words in poetry can indeed do much to engender change and project the inner cravings of the poet

In the case of Kukogho, Words project anger, disappointment, frustration, dashed hopes, family abandonment, and an inner urge for change, thus showing that words crafted in the rhyme and rhythm of poetry can do much. The words of his poetry are steeped in the droppings of the anguish of the poet’s heart. These words, without being spoken, scream stridently for the attention of society and call for the redress of its imbalances. Words, according to Kukogho, can do much.

Despite the elegance, finesse and alluring cadence of the rhyme and rhythm of the verses which announce a sophistication of style and aesthetics, Kukogho does not lose sight of the critical issues of deprivation and distortion that pervade the land and which require urgent redress. The poems seethe with politics and express the angst and frustration of the poet with the existing political order.

Where is the Breath of Fresh Air?’ (27), for instance, is classic, for its biting and scarring sarcasm. The allusion to the deceptive promises of the campaign of a “breath of fresh air” by then President Goodluck Jonathan is clear and unambiguous, especially weighed against the background of the poet’s masterful stylistic and aesthetic management:

A hundred and sixty million noses sniffing the air,

Searching for the fragrance that is not there,

They go sniff; father, mother and the brood,

For they said our Shepherd had Luck, he was Good.

A breath of fresh air we sought, in the dark we groped,

Unlit candles in our calloused hands, we hoped

For the vagrant wind to blow in the fragrance of roses

And sweep away the stench pinching our mucused noses

....now our noses are twisted like the aged oak in my village.

We have twisted them, first with hope and now with rage.

We smell nothing now for our runny noses are stopped

By the odor of the farts their buttocks have dropped.

We have fallen from the heated pan into raging flames

And our souls have been scared from our hungry frames,

Now, we hear not for our ears are deaf from the thunder

And we flee for we are yet unready for the journey under

Is this the breath of fresh air our noses sought

When we spoke with one voice, daring their wrath?

I smell no fragrance but the aroma of barbecue on fire,

Barbecue of brothers and sisters grilled with their desire

This poem, with its suffuse of fitting imagery, highlights the lofty expectations of the people from their leaders but shows that the mightier those expectations, the mightier they have been dashed. The people have been repaid with a situation worse than the politicians promised to redress, ‘ we have fallen from the heated pan into raging flames’.

The poet does not however believe that this will go on forever;

‘I smell no fragrance but the aroma of barbecue on fire

Barbecue of brothers and sisters grilled with their desire’

In a similar way, ‘The Voters’ explores the theme of politics where politicians only come out to canvass votes only to disappear from the radar of performance. Poet turns into an advocate here by exposing the deceit of the political class which he believes can only be resisted by the consciousness of the electorate who must make informed choices:

So when you come to me now, smiling like a circus Gorrila

(One moment away from the comforts of your Villa),

(Note the perfunctoriness occasioned by the parenthesis)

And you talk to me of sweet nothings, I listen mute,

For I can play only discordant tunes on my flute. (29)

‘Of Speaking Thumbs and Fists’ (30) similarly paints a picture of frustration of repeated dashed hopes occasioned by the folly of the political elite, and the acquiescence of the placid aloofness of the docility of the people.

‘And so when they ran the race

We only looked and hoped from our place

Alas, in the dark, short corners they laid

And ran not on the tracks we made’.

While the poet concludes that the lack of vigilance by the people will continue to rob the political process of the needed credibility, he believes, in even a more significant measure, that this will not endure because the outcome of political robbery is frustration which inevitably leads to anger and violence:

They have robbed us while we slept.

The fury of the fist is what we have left.

To the streets we go, our fists shall speak.

We’ll make our marks with the stick

Since they have made deaf and dumb,

The marks we made with our thumb,

And speak with did; smoke tells the tale,

For we left him behind on our trail.

We left behind too, cries and blood-

The ink that fuelled our angry sword,

Now smoke engulfs our land, anger is spent,

But tomorrow is still crooked and bent.

On the whole, we could say that there is diversity and profundity of thought and theme that deepen the thematic thrust of the work anchored on the strength and depth of aesthetics. The poet shows that poetry is both expressive and at the same time escapist, leading to an outpouring of the inner pangs of the poet.

Although some of the preoccupations of the poet could be autobiographical, they are nonetheless applicable at a societal level as reflective of what the larger Nigerian society must atone for. In “You Made Me What I Am” the poet depicts the harvest from the untended souls of youth abandoned to the wiles of the vicissitudes and vagaries of uncertainties by the callously designed imbalances of the political and economic order that favours the rich but not the poor. The rich in their haughtiness abandon the poor who turn round for vengeance, forcefully calling for attention and the due payback of callous ‘fathers’ who abandoned their ‘sons’.

In this collection What Can Words Do, Kukogho announced his unpretentious arrival as a voice we will continue to listen to for years to come in the literary firmament.

Professor Gbenga Ibileye is a language expert and university don at the Federal University Lokoja, Nigeria, where he is the General Studies coordinator at the Department of English and Literary Studies. His decades of scholarship span many institutions in Nigeria and Senegal.

You must be logged in to post a comment.