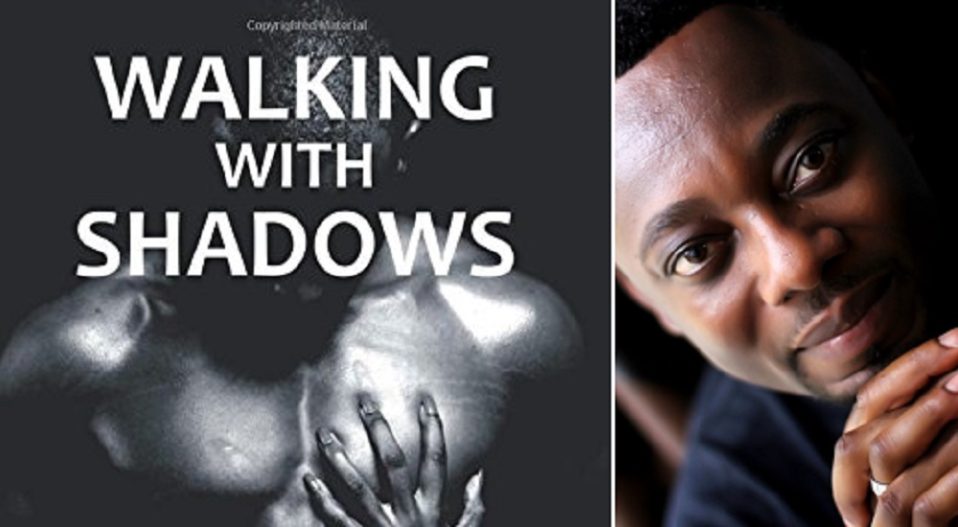

AUTHOR: JUDE DIBIA

GENRE: PROSE FICTION

NUMBER OF PAGES: 216

PUBLISHER: Lulu.com

DATE OF PUBLICATION: 2016

ISBN: 141161934X (10), 978-1411619340 (13)

REVIEWER: Eugene Yakubu

Controversial novel by Jude Dibia ‘Walking with Shadows’ emerged at a time when Nigeria was battling with the idea of homosexuality as an “unAfrican” perversion; this bold narrative dares discussing issues that many Africans would rather toss under the rug and pretend it doesn’t exist. Dibia’s novel is unarguably the first Nigerian novel to deal sympathetically with a gay character. Even though earlier Nigerian writers hint at queer presences in their narratives they however bury the queer character and his gender role versatility to make way for a strong, masculine image of a heterosexual male which practically overrode the need to depict an alternative sexuality in fiction.

But even so, Jude Dibia broke loose of traditional and topical themes in African literature and toppled the stale discourses of post colonialism, poverty, history to reconstruct brand new tales that creates a space for the queer body in literature.

This book will give the voracious reader a break from overstayed sociopolitical themes of cultural nationalism by conservative authors; drilling a space for the emerging sexual identities that have not been placed within the essentialist culture— the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual and the Transgender. Dibia plays with polar figures of sexuality and gender and recognizes the fluidity of individual sexual lives. Dibia proves that sexual orientation has more to do with personal happiness and sexual pleasure than with the material basis of procreation.

This debut narrative is the first of its kind in Nigeria and it makes obvious the visibility of the LGBT community in Nigeria despite growing homophobia and violence committed against people with a different sexual orientation. As much as this book cannot be regarded as superb art for its casual literary style and oversimplified plot evident in the superfluous sentence structure and the excessive usage of gerunds; it can securely stand as a grand narration because of its unique and fierce attack of rigid polar and conservative ideologies. The theme of ‘Walking with Shadows’ is a timely effort in literature, for trying to submerge doctrinaire hegemony, replacing socially named and presumably stable categories of sexual orientation with a new fluid movement for varying individuals— (homo)sexuality, bisexuality.

Dibia’s audacious pro- gay arguments may sound manipulative, nonetheless they criticize socially held doctrines as not necessarily “truth” because it is widely accepted but just another possible view to an idea.

Adrian argues that he is gay; he argues “I’ve always been and I’ve always known. Yes, I am married and I have a kid but take away who and what I am” (50). Dibia plainly said that Adrian sexuality wasn’t a habit, “it was biological… he had always been this way” (53). However, Dibia’s assertion can rightly be criticized as flawed because he proffers psychological factors in the narrative that might have all contributed in making Adrian gay.

The narrative reaches a humorous climax with Adrian going through spiritual cleansing from a pastor with prayers and violent lashings as arranged by his brother who thinks Adrian is “sexually confused” and needs to be cured of his demons (homosexuality). The fact that Adrian’s homosexuality is read as a spiritual attack is ridiculed by the author to depict the degree of homophobia in Nigerian societies and the violence to proffer the heinous effect of homophobic acts.

‘Walking with Shadows’ depicts the visibility of the gay community in Nigeria despite thriving homophobia and hate. It hints that even though African society have always portrayed African culture to be strictly heterosexual and free from the West’s perversion, however LGBT people do exist, but may be “closeted” for fear of hate crimes and aversion. This novel shows that the absence of evidence of homo-social acts in African societies doesn’t necessarily proffer for an evidence of absence and there may however be “closeted” homosexuals like Adrian who are forced to practice heterosexuality because of its societal acceptance and popularity; but have no inane drive and feelings for the opposite sex.

This narrative is significant for being the icebreaker for queer narratives and queer themes in Nigerian fiction. For now, the silence among Nigerian writers about queer sexualities is not only eroding but turning into polyphony.

This novel captures what it means to be a homosexual and “different” in an African setting, always having to risk being found; by society, family and also having to repress and suppress one’s spontaneous feelings and emotions. Dibia’s novel is a force to reckon with in contemporary African fiction. Its appraisal of issues many authors would have considered nether and trivial has tacitly created a backdrop for queer characterization in Nigerian literature.

Dibia is undeniably a sound writer and a cunning debater; he successfully carries his pro-gay arguments right to the end of the narrative and even had his protagonist Adrian abandon his familiar lifestyle, profession, family, wife and daughter to a Western country with less homophobia and a space for people like him and praying that homophobic Nigeria “would be a different place… and its people would be more receptive and less judgmental than they were now” (202).

Even with the fragile themes and issues raised in Walking with Shadows, Dibia’s mastery of art is evident in his ability to sustain his striking arguments to the end and successfully fighting homophobia by parading a likable character Adrian, thereby, creating a secured space for the LGBT community in fiction and the society, and most importantly submerge and invert fixed gender roles, immersing it in flexible and mutable possibilities.

Walking with Shadows is educative as well as enlightening; it discusses gender, sexuality, identity and non-normative bodies in the society. It is a recommended text for readers bored by the monotonous themes of earlier Nigerian authors.

Worth the read, only hope the novel would be half as good. moreover, what’s this thing about homosexuality in virtually every African novel? its obvious the white man has eventually recolonized us with this strange notion of a native homosexual identity. i believe this writers are only concerned about

being the good “gay writer” instead of the good writer.

Contemporary African literature is highly manipulative now, authors up and about trying to tell readers how to think and live their lives. Who does that? we should give art a chance first, before any theme or story.

good review Eugine Yakub

Thank you for your comment @etekaemmanuel:disqus. The issue of whether or not books tell us what to do and how to do it has been in the front burner of literary discourse for years.

“The collective goal of literary fiction is to capture all of what it means to be human.” {cant remember the author of the quote]. In capturing what it means to be human, the writer can only write from his/her own experiences and sets of beliefs personally held or observes. In the end, all these may look like preaching at the reader, while the writer is just telling.