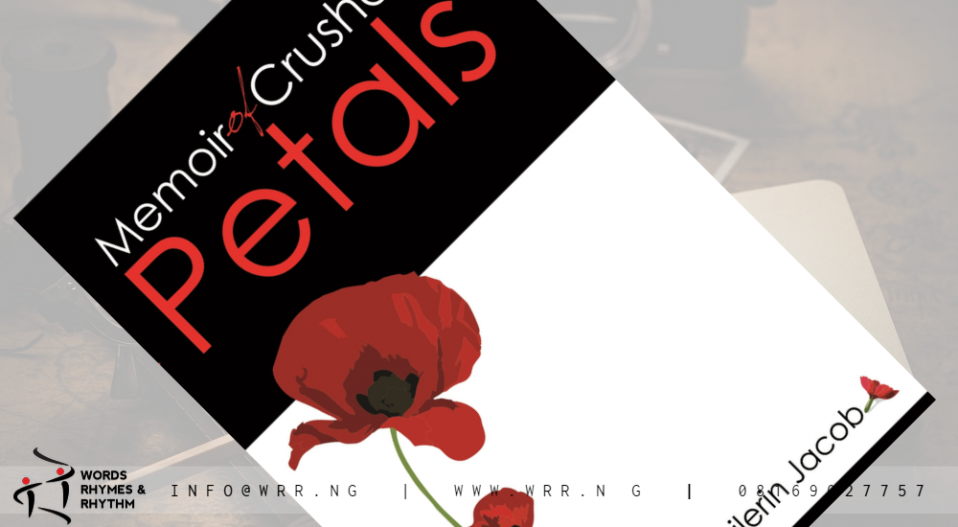

TITLE: MEMOIR OF CRUSHED PETALS

AUTHOR: PAMILERIN JACOB

GENRE: POETRY

NUMBER OF PAGES: 100

PUBLISHERS: WORDS RHYMES AND RHYTHM

YEAR OF PUBLICATION: 2018

ISBN: 978-978-963-998-4

REVIEWER: Oyindamola Shoola

Without doubt, Pamilerin Jacob is a phenomenal writer whose words cut through many norms that have gotten too comfortable in Nigeria. He writes boldly and unapologetically with the type of attitude that many pioneer Nigerian writers like Odia Ofeimun did.

Pamilerin writes vastly on topics such as; justice, mental health, terrorism, religion, and death, amongst many.

In the poem titled My Bible, My Skin on page 16 of Memoir of Crushed Petals Pamilerin ends with the following lines:

“don’t be depressed, don’t ever tell them you are depressed

do remember to hide your pain under your armpit

Nigerians are never depressed; it is the white man’s disease

don’t be a fucking bastard…!”

Pamilerin’s writes with a raw honest that provokes conversations on topics that many Nigerians shy away from discussing, especially mental and psychological health. Mental health in Nigeria is not taken seriously until a person “runs mad,” and even when the person does, the diagnosis that many Nigerians give is spiritual. He or she must have done something to displease God or “the gods.” It is a shame that psychological health is also not taken as seriously as it needs to be.

When someone confesses that they are depressed, they are told “pray” and “fast” without being counselled or questioned about the possible cause(s) of their depression.

Once, I read a joke about a Nigerian police officer who saw a young man that wanted to kill himself by jumping over a bridge. Upon sighting the young man, the police officer says, “If you kill yourself I will shoot you.”

This joke inferred the type of punishment associated with expressing emotional or psychological distress as a Nigerian. It is similar to the story of a young woman that I read recently. She confided in her mother that a close family member raped her and out of frustration, she tried to kill herself on three occasions. Instead of receiving consolation from her mother, her mother says that if she dies, it is one less burden on the already poor household.

As Nigerians, there is this expectation to have a hard skin against emotional, psychological, and mental challenges, especially after dwelling in the midst of daily hardship and surviving. So, in an attempt to protect this resilience that we are expected to associate ourselves with, instead of developing it individually, we break people and worse, force them to be silent about their brokenness.

In Pamilerin’s words, we tell them, be quiet and “hide your pain under your armpit.”

Pamilerin’s writing on the topic of mental health also raises the need to provide counseling facilities in Nigeria. Many so-called “counselling-centers” or “counsellors” in educational institutions that I have witnessed are dysfunctional and without proper training to serve the people in need.

Additionally, I think that Nigerians who utilize mental and psychological health resources also bear responsibility in breaking these taboos and stereotypes. When we are open to discussing our experiences positively, we create an atmosphere for others to be honest about their feelings and state of mental health. We are all responsible for minimizing the shame that is associated with being vulnerable and accepting help.

In many poems, Pamilerin also discusses masculinity and how men have unrealistic expectations regarding their emotions. In a poem titled Real Men, on page 28, Pamilerin writes;

“five, 4

3

two days ago, I saw a snail sniffing salt like coke,

he had no shell I asked him why

he had chosen to forsake himself, why

he had chosen to swallow fire

he told me, shells were for weaklings

that real men eat poison and don’t die, that

real men will never ever ever ever ever ever ever ever ever cry

even when you crush their testicles”

Only if we would spend the same energy we use in rubbing men’s minds with ego, to actually address the issues that we teach their egos to protect in the first place. The childhood of many boys are stifled with this mentality of what it means to “be a man” in a way that forces them to make worse decisions in the face of admitting weakness. Pamilerin shamelessly reveals vulnerability through his poems, and I find this shamelessness so powerful, and inspiring.

In part III of a poem titled SOS on page 45, Pamilerin shares a response he received, that I will assume was to address some sort of distress. He writes;

Reply (Dec 1, 12:37pm):

Hi Jacob,

I need you to arrange your thoughts;

that’s all I need you to do

put them in folders, and keep them

in a safe place till we can talk,

can you do that for me?

I can relate to this, and on one side, it makes me very appreciative of many people who have become a support system for me. Recently, in one of my very stressful moments, I ranted to my sister, and she told me almost the same thing that Pamilerin wrote; to write a list of my thoughts and all the various places I am actively involved in. I ended up writing 4 pages (without double space), stating each work title and all my roles underneath. Although, these were thoughts written out of distress, when I finished writing I said to myself “Wow!” with this feeling of pride because, for a long time, I had not reflected on my actions, so I did not see my own impact. It was an absolutely different experience arranging my thoughts and seeing my own reflection on paper.

On page 47, in the poem titled On Why I Write, Pamilerin writes,

“every day, death is postponed

because

of an unfinished poem”

This poem reminds me of a conversation I had with a friend about having mental and emotional stability. My friend said that emotional and mental stability comes from having purpose and often times, people think that the sense of purpose comes from the things that we love only, which is not true. Purpose can be that job you don’t like. He said, although you hate the job, you still wake up 6am every day for the purpose of preparing for that job.

When people become emotionally distressed and fall into depression, many of them no longer find purpose in their actions and their living.

So, if they have suicidal thoughts, they will say, why am I living? As a friend, a sister, a lover, a counsellor, you can such people to find or to remind them of their purpose. In the poem titled On Why I Write, although, an unfinished poem seems like nothing, it gives a purpose to living.

In another poem, Pamilerin distinguishes himself again in his approach to topics such as “Jungle Justice.” He reveals human nature and how people make irrational decisions in urgent matters until it has to do with something or someone they love. On page 79 in a poem titled Brain Freeze, Pamilerin writes,

“when your child steals from the pot,

drag him to the town square

douse hum in petrol, and tell

a bystander to light a match”

His descriptive words and the visual imageries with his words, make a reader feel disgust about this idea of jungle justice. Pamilerin continues,

“if he tries to run, pick up your sins

hide them in stones and throw

throw until his skull is crushed,

and petals

fall

out

like spit from a bickering mouth,

target that space between his eyes

and slam a stone into it, as though

aiming for a spider, slam until

his mouth foams like a cup of beer

because he has committed a great treachery

and you,

you are spotless, like a cheetah…

you fool.”

Pamilerin makes references to religion, sometimes, in an appreciative manner, and other times, in sarcasm. In the poem Brain Freeze, Pamilerin references the harlot that Jesus prevented from being stoned to death. I love the phrase “you are spotless, like a cheetah… you fool” because it samples how skilled Pamilerin is, in moral didacticism while combining shadiness and literary devices.

In another poem that references religion titled Trance on page 22, Pamilerin writes,

“I am malnourished because

god loves to mask sorrow

as a test:

kill your son, slice your wrists

swallow office pins, swallow

the masquerade’s penis…

trust me, I will give you stars

for children if you obey me,

when you slice your wrist

I will turn your blood into wine,

we will drink of it together

then will I turn you into dust”

You will see traces of Abraham sacrificing his son and Christ sacrificing himself. In this poem I also sense a mockery of the fact that, we can believe that a man almost killed his own son because God told him to do so, and we can also believe a man who says we should drink his blood and eat is body. These men are not crazy in our eyes, and many of us live to worship them.

Pamilerin gives a voice to strange thoughts.

He also gives a voice to provide liberation to many individuals like a character named Aina on page 75. He discusses gender inequality and many other challenges that women face, especially in marriages. In a stanza of the poem titled Aina, he writes,

“enslaved from heaven, aina was born

with an umbilical cord round her neck

that tightened

every time she tried to tell her husband

she too, was human.”

I admire Pamilerin’s reference of Yoruba culture in this poem with the name Aina and creating an extended narrative of the name’s translation in light of issues like gender inequality.

I am extremely impressed by this anthology, and I am very proud of Pamilerin Jacob. Just when many people are settling for the norm, we have writers and thinkers such as Pamilerin who is not afraid to be distinguished. He is one who takes his writing to heart and despite his level of understanding and knowledge, he is humble enough to learn. You will see his humility in his constant reading habits to develop his craft despite how good he is already.

As one of the mentees, in the first cohort of the Sprinng Literary Movement mentorship programme, Pamilerin Jacob displayed a type of commitment to developing his skills that is hardly found in many young writers today. Upon being accepted to the Mentorship Programme, unlike other mentees, who received mentors in the genre they were interested in, I had challenged Pamilerin to be mentored in another genre other than the poetry which he applied for. He proactively took on the challenge and was mentored in essay writing by Adekunle Adebajo who is an award-winning poet, essayist, public speaker, and journalist at the University of Ibadan. In Adekunle Adebajo’s appraisal of Pamilerin Jacob after the SLM mentorship programme was concluded, Adekunle wrote:

“Pamilerin is smart, humble, patient and eager to learn. His craft is excellent. I had a great time communicating with him. He knew so much already, but I’m certain the sessions were nonetheless beneficial to him.”

With writers like Pamilerin Jacob in my generation, I think the world of literature in Nigeria is bound to be a better and greater than what our ancestors left behind.

You must be logged in to post a comment.