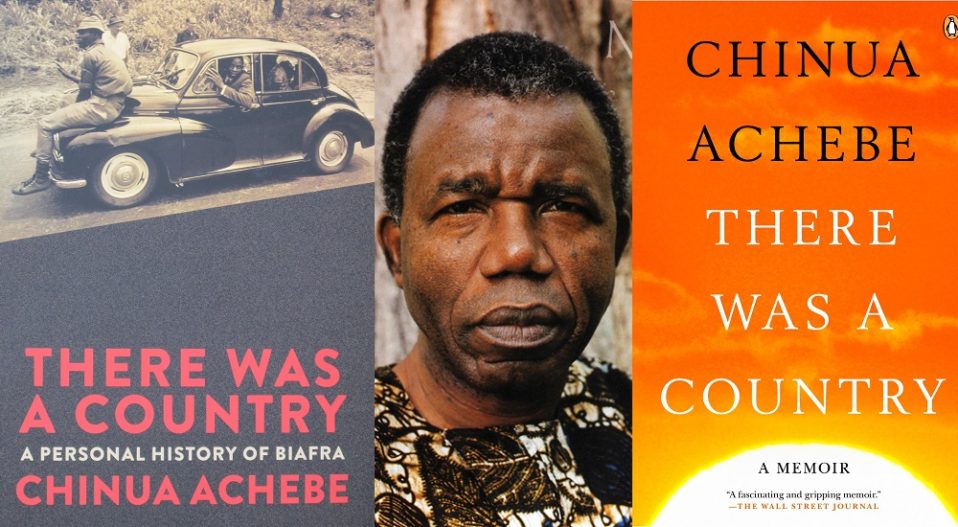

Title: There Was a Country

Author: Chinua Achebe

Genre: Memoir, Historical Narrative

Publisher: Penguin

Year of Publication: 2012

Number of Pages: 352

ISBN: 978- 1- 846-14792-0

Reviewer: Eugene Yakubu

One notable event which has sparked the inspiration for novel writing in the last twenty years is the Nigerian civil War of 1967- 1970— the context of Achebe’s There Was a Country. Unlike other historical and literary documents on the Nigerian Civil War, Achebe’s account is undeniably a historic and literary force to reckon on in contemporary Nigeria. In There was a Country, Achebe reawakened the sleeping ghost of Biafra at a moment when the hostility over the war in Nigeria is dying out but the undying mission of seceding from Nigeria is still bracing.

This matter- of- fact, straight- in- your- face, ‘who- cares’? (scoff) literature has a million and one reason to lure you into the bookstore— history, religion, art, biography, culture and poetry all enclosed in this portable time machine which takes you years into the future of Nigeria and directly plunges you decades into the less talked about and crookedly buried past.

This matter- of- fact, straight- in- your- face, ‘who- cares’? (scoff) literature has a million and one reason to lure you into the bookstore— history, religion, art, biography, culture and poetry all enclosed in this portable time machine which takes you years into the future of Nigeria and directly plunges you decades into the less talked about and crookedly buried past.

‘Chinua Achebe’ is a secured name in the literary heaven. The name alone reverberates with literary thunder, strutting gracefully in poetical robes and lyrical prowess, a countenance of rhetorical acuity and aesthetic charm—- Achebe has never ceased to amuse his ardent readers since Things Fall Apart with bewitching proverbs, grand language, sublime narration and pricking ideologies.

However, despite the sophisticated tone of this memoir, Achebe warns “[m]y aim is not to provide all the answers but to raise questions, and perhaps to cause a few headaches in the process” (228)

Ever wondered why Wole Soyinka discouraged Achebe from writing this book There was a Country? ….Uhmmmm! Clueless right? Well… get ready for “headaches” in There was a Country. The answer is buried right in this literary bible and you don’t have to go far to exhume this fragile history than to push yourself right inside the historical cave that many would rather step on. Hence, dogged Achebe— even though Soyinka “…wish[ed] he had never written, that is, not in the way it was” (cited in Gashua, 2016), says he must write this single memoir “for the sake of the future of Nigeria, for our children and grand children, that I feel it is important to tell Nigeria’s story, Biafra’s story, our story, my story” (3)

Well, sit back, flush out your stale history of Nigeria and get ready for an adventure into one of the rarest and most distorted history of Nigeria, of a course, a people and a nation, a prowling ghost and a hostile Nigeria—- Biafra! Yes, I just said it Biafra, how ghostly is Biafra? Not entirely, according to Achebe for the war for secession might be lost some six decades ago with the slain soldiers on the field but not the “struggle”, the “cause”— it lives on, it is happening right now apparent in Nigerian politicking and the contemporary politics of secession from the South East which is unfortunately gaining momentum daily.

Achebe has already written extensively about Biafra in poems, short stories and essays. There Was a Country draws on much of this material. A dozen poems are dispersed throughout the text. Why then, has he chosen to write this politically inflected memoir, 40 years later? Achebe himself comments that “there is some connection between the particular distress of war… and the kind of literary response it inspires”. It would have been impossible to write such a historical work in the midst of conflict. But perhaps, more importantly, this book is Achebe’s exploration of the disappointments of the post- independence era, and a testimony to the aspirations of a dwindling generation. ‘The Biafran Story’ is well written by the master story- teller with the graphic simplicity and factuality that rarely foreshadows any impending ill omen.

When you talk about proverbs in African literature, Achebe is undeniably a force to reckon with. For Achebe a proverb does just more than communication, for “they are the palm oil with which words are eaten”. They keep the reader at attention so as to digest the meaning of the words. In There Was a Country, Achebe dropped a handful starting the novel beguilingly with “the man who does not know where the rain began to beat him cannot say where he dried his body” (1). Isn’t it beautiful that Achebe combines local flavor with foreign words to domesticate the English language for his kiths and kins in Africa? This is a rare fit and the reader is sure to have enough of proverbs like this sprayed all around the narrative.

Some might scoff at my reference to There was a Country as a “literary bible”; however, a sneak peak at this beautiful piece of art will give you the whole genres of literatures neatly knitted in this one extraordinary and timeless book. This grand piece comes with assorted lines of poetry on different topics swirling around Biafra and the Civil war. Moreover, Achebe “made the conscious choice to juxtapose poetry and prose in this book to tell complementary stories, in two art forms” (2). Interesting poems like 1966, Generation Gap, Benin Road, Biafra 1969, The First Shot, We Laughed at Him, Vultures, Air Raid amongst many are doled out momentarily in the narrative for the reader’s pleasure and as a purgative for the heinous and bizarre scenes of war, malnourished children, slain soldiers, splattered skull and nauseous atmosphere captured in the narrative.

Achebe infused relevant quotations from notable war historians like Harold Wilson, Herbert Ekwe- Ekwe, Dan Jacobs, Arthur Schlesinger, Andrew Brevin, David MacDonald to garner his fragile assertions finely. He might just be recreating history, but this is a different kind of history from the popularly circulated one. Achebe pukes out his aggression and distaste on Nigeria with blatant disregard for authority while vehemently avoiding sugar- coated truths. However, Achebe warned that his memoir is a “personal history of Biafra” and it is strictly subjective. Therefore, for Achebe, Former Head of State Yakubu Gowon reference to his narrative as “propaganda” is baseless and presumptuous. Gowon, a major figure in the civil war talking about There was a Country in an interview said:

Though many books had been written about the Civil war, none had been as controversial as that of Achebe which accused me and chief Awolowo of genocide against the Igbos. Nothing can be further from the truth, because every decision we took was for the interest of a united Nigeria

This of course is a daring and courageous memoir; Achebe scorns at political systems in Nigeria and fiercely proffers hard- to- believe evidences of a “Northern military elite’s Jihadist or genocidal obsession” (232) by the Nigerian army to wipe out the supposedly vulnerable Biafra.

However, despite the historical and literary significance of Achebe’s There was a Country, Achebe practically refused to let sleeping dogs lie with his prejudicial comments and sided arguments about the Civil war at a moment when Nigeria is about to experience relative peace; then comes There was a Country with an undaunting obligation to uncover gory scenes and vile stories— some of them outrightly farfetched, others valid; which unfortunately proves that Achebe writes his personal narrative as an Igbo writer instead of a writer who is Igbo. The problem with his style is painting a group of actors in “Nigeria’s problem” all virtue and the others all vice. It is difficult to believe that the virtuous people did nothing wrong; and the all vicious did nothing right. As some memoirists contend, if you are writing about someone who did you wrong, don’t hide out his good sides.

Nevertheless, this must- read narrative is recommended for persons eager to dig the history of the ethnic hostility, civil unrest and contemporary political tussle in Nigeria. It covers Nigeria’s history from the pre-colonial, colonial to the post- colonial era, reconstructing notable and prominent events that are a pointer to contemporary politics in Nigeria. There was a Country is educative, informative, entertaining and historically refreshing— and yes! It deserves a regal space in every cultured mind and bookshelf.