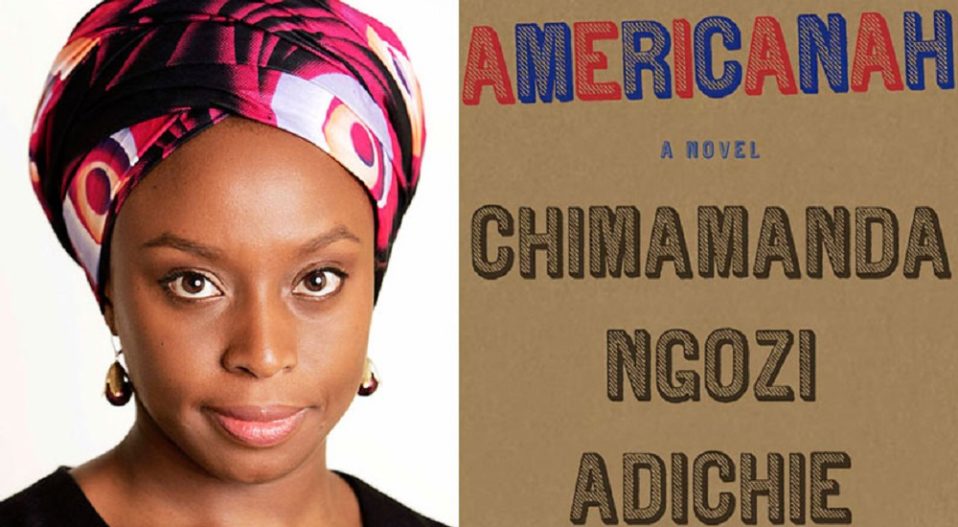

Title: Americanah

Author: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Genre: Prose Fiction

Publisher: Farafina

Year of Publication: 2013

ISBN: 978- 978-51084-3-9

No. of Pages: 477

Reviewer: Nket Godwin

It is no doubt, Chimamanda’s narrative prowess. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the author of Purple Hibiscus, Half Of A Yellow Sun, The Thing Around Your Neck, etc, has emerged with another intriguing, fascinating, pathetic yet enchanting tale that will leave the readers flowing with every page and chapter of it… Chimamanda (who Achebe described as “another leading legend endowed with the spirit of ancient storytellers”) is indeed one with which the world will look up to in terms of literary melody. She is a writer which, if engaged with, will take one’s imagination to a different dimension; her narrative, as Achebe described, is imbued with wit, saga, drama and fiction metamorphosed into non-fiction. If engaged with Chimamanda’s Americanah, one would not hesitate to flow with non-fictive issues of everyday’s life. This has everything to do with her gusto in colouring her characters with human intelligence in dealing with our everyday issues.

Chimamanda’s Americanah is structured in fifty four chapters and five hundred and fifty six pages. Every chapter carries a well-developed plot unfolding an exciting story, themes and moral lessons. The plot is further bisected into eleven parts with long and short chapters.

Americanah is also flavoured with literary terms and figurative expressions. Literary terms like: imagery, narrative technique (which is third person or omniscience), dialogue, characters and flashback. Figure of speech like allusion, metaphor, simile, irony, etc. It can, if critically viewed, be described with many appellations, like: satire, epic, romantic (ribald), and, overall, it can be called didactic novel. Viewing Chimamanda’s Americanah as a satire – being a work of art that makes critical ridicule of a society, group of people, human being’s way of life, institution, government with a view of making moralistic correction – it successfully makes satirical assertion on political, cultural, environmental and racial perception in our everyday activities. Chimamanda’s Americanah makes these assertions through some of its minor and major characters, like The General, who is portrayed in the novel as a military personnel who only involves in politics just to syphon and embezzle the funds; a character whose live hangs on gallivanting about, carrying young girls and drinking. Looking at his trait, as a character who also help unfolds the novel’s plot – though a minor one – it can be deduced that he is used to symbolize the period of military take-over of power, with the ambitious aim of only tasting the cake. Also there are dialogues within characters in the novel which also allude to the epic period of some of the military arbitrary rule in the country. E.g the utterance by Aunty Uju. Aunty Uju moans, blamingly, her state of hardship and hard cost of living in America; she moans her connubial nut, the extent of discrimination in her work place which is nothing other than the itchy claw of racism. She refers it to Mohammadu Buhari, Babangida and Abacha, who, with their obnoxious, despotic and dictatorial form of leadership, end up forcing the citizens out of the country, thereby forcing them to hang helplessly on the claws of racial discrimination. Chimamanda, through her character – Aunty Uju – captures thus:

Americanah is also flavoured with literary terms and figurative expressions. Literary terms like: imagery, narrative technique (which is third person or omniscience), dialogue, characters and flashback. Figure of speech like allusion, metaphor, simile, irony, etc. It can, if critically viewed, be described with many appellations, like: satire, epic, romantic (ribald), and, overall, it can be called didactic novel. Viewing Chimamanda’s Americanah as a satire – being a work of art that makes critical ridicule of a society, group of people, human being’s way of life, institution, government with a view of making moralistic correction – it successfully makes satirical assertion on political, cultural, environmental and racial perception in our everyday activities. Chimamanda’s Americanah makes these assertions through some of its minor and major characters, like The General, who is portrayed in the novel as a military personnel who only involves in politics just to syphon and embezzle the funds; a character whose live hangs on gallivanting about, carrying young girls and drinking. Looking at his trait, as a character who also help unfolds the novel’s plot – though a minor one – it can be deduced that he is used to symbolize the period of military take-over of power, with the ambitious aim of only tasting the cake. Also there are dialogues within characters in the novel which also allude to the epic period of some of the military arbitrary rule in the country. E.g the utterance by Aunty Uju. Aunty Uju moans, blamingly, her state of hardship and hard cost of living in America; she moans her connubial nut, the extent of discrimination in her work place which is nothing other than the itchy claw of racism. She refers it to Mohammadu Buhari, Babangida and Abacha, who, with their obnoxious, despotic and dictatorial form of leadership, end up forcing the citizens out of the country, thereby forcing them to hang helplessly on the claws of racial discrimination. Chimamanda, through her character – Aunty Uju – captures thus:

“[…] The other day the pharmacist said my accent was incomprehensible.

Imagine, I called in a medicine and she actually told me

That my accent was incomprehensible. And that same

Day, as if somebody sent them, one patient, a useless

Layabout with tattoos all over his body, told me to go

Back to where I came from. All because I knew he was

Lying about being in pain and I refused to give

Him more pain medicine. Why do I have to take this

Rubbish? I blame Buhari and Babangida and Abacha,

Because they destroyed Nigeria”. (Chapter 21, P 253).

It is also a kind of political satire, on the part of the writer; it paints the sardonic mode of leadership in an humorous, awkward, but pathetic way. Chimamanda’s Americanah can be termed “satire” because, not only does it successfully treat romantic issue, but also dives into political terrain, both in Nigeria and America, being its spatial settings. It satirizes General Abacha’s arbitrary regime – though he is not presented in the novel as a character; but through the characters’ emotive states, their dialogues, etc, we get to know the prevailing political atmosphere as at then. This also leads to the era during which the piece is set.

It further goes forward to satirize American politics, which is cloaked with racism of all sorts. This is shown through the novel’s heroine, Ifemelu, who, following the itchy tongue of military rule in Nigeria, flown to America to complete her education, but inversely she was weighed down by racism. Racism is the judgement, often cruel, of people, especially those from other part of the continent, by their colours, rather than seeing them as humans. This, according to the writer, is the norm and tradition in America. Chimamanda, through Americanah, successfully underrates racism to the point in which, in America, the physical disposition of one’s hair also determines people’s view. Now is that not sarcastic and humorous? Hair, which one will term ‘ordinary’ is consciously rated as a determinant of undue discrimination and misconception of one’s background: historical and continental. Why is it that these conceptions always garner more feathers in non-African countries than African countries – most often Americans? I do not necessarily think Africans are what alien minds think they are. We want the world to unite, we want the world to be equal; yet they keep gazing at us with contempt blinking in their retina like a lush spectrum.

Chimamanda’s Americanah goes further – in one angle as the backwash of racism – to disclose the form of life in America by non-indigene blacks; a form of life which is proffered as an option for one desperately in need of a way of living. Ifemelu, being the novel’s heroine, is one of the victims of this form of living, impaled by joblessness. On the same hand, the state of joblessness in America, as presented in Chimamanda’s Americanah, can be gazed through the lens of racism. Ifemelu toiled from place to place, office to office in search of a reliable job, but unfortunately for her, what she finds is discrimination and the piercing fang of racism. Thus she had to go into massaging, offered to her by a whiteman, which, after she accepted it, denigrated her humanity and sense of value as human – and also as a woman. She had to hate herself for doing such a sardonic job; offering herself to a man to scrub fingers about just because of the offer of hundred dollars. This excerpt from Chimamanda’s Americanah teaches paramount moral: let’s not be too desperate, or let not our desperations overshadow the unpleasant result of the actions we are about to take. Also, to cater for her life in America, she decides to take a job as a babysitter. Ordinarily she wouldn’t have accepted such offer, but because she is desperate and needs morning, she had to.

Also in Americanah there is issue of marital demonstration. One of the central theme in the novel is “connubial”. The relationship between Aunty Uju and The General, which – one may think is peradventure – resulted to conception, and unfortunately the baby was born without a father, as a result of the untimely death of the General in an assassination. The relationship between Aunty Uju and The General is build on the whim for material welfare and clout, which is not exception of this contemporary era: young girls following big men about because of money and political clout. It ends, according to the novel, the way it – if care is not taking – often ought to end. Also, in the novel, Ifemelu and Obinze were in a very love-bound relationship. The relationship help unfolds the plot of the novel: its exposition, zenith and denouement. Though the novel bears a complex plot (starts at the middle, where Ifemelu was preparing to return to her homeland, goes to the beginning, thus retraces the root of Ifemelu and Obinze’s relationship during their teenage moment in school; flashed back to the middle, accounting for Ifemelu’s forms – often despairing and laden asperities – of life in America, cloaked on racial aspersions. Examining the plot of the novel: its exposition and resolution – apparently it adds to the novel’s aestheticism – one would admit that it ends abruptly, leaving the readers spellbound in suspense. Ifemelu and Obinze, after their educational toil in America and England, encountered the crux of their love; however this occurs as a result of the decision they made. Ifemelu, while in America, abandons the reputation of their love, thus goes over to other men in America; fatefully the nascent relationship is temporal; it often turned instable until she came back to her homeland.

The memory of their love momentarily haunts her. This often occurs whenever there to be a turnover in her present relationship. Is this – the momentary, or let me say, sincerity of her love with Obinze – responsible for the consecutive fate of her new-found love in America? Obinze, on the other hand, made the decision, which later seems to him as a ‘regret’, because he thinks he is impatient with waiting for Ifemelu’s return. On the other purview, it can be traced to their temporary, abrupt end of refreshing messages, phone calls and emails, which reminds them of their unity and romantic affair. Critically, we can deduce that this – the abruptness in their relationship, propelled by distance – made Obinze, after being a well-known businessman (wealthy and hearty), to take the drastic decision of getting married. This, after Ifemelu’s return, makes them face the adversity in their relationship, which makes Obinze take the drastic decision in his marriage. With his desperation to be with Ifemelu, he decides to divorce his marriage just for them to crawl into the shell of their Secondary-days love – if chance will give a space, get married! But as a literate someone, I think, why should Ifemelu, just for love, congealed her mind to destroy another woman’s marriage? She should have disclosed its backwash to Obinze, who, in his desperation – though educated – seems like a child. This rhetoric often makes me ascertain that marital issue is never all-through an institution which can only be run or say “administered” by literates. The issue of love and relationship have a certain precept which can be learnt through experience and philosophical study.

Furthermore, the ending of the story is suspense-brimmed – suspense-brimmed because one would be left wandering and wondering on Obinze’s wife’s reaction – or (to render a spectator’s reputation) she would pardon the emotion of love and go her own way. One will always duff for Chimamanda’s prosaic prowess; especially her narrative, descriptive as well as expository tendency in stripping faction bare in fiction. Her tale, Americanah, is an epitome of this. It’s an enchanting tale encircling our everyday’s life. Thus, I urge literature readers as well as the world to take a copy of it and sip; even gulp, for it’s philosophically sugary. In it, you see faction walking hand-in-hand with fiction, making it a clear emulation of the contemporary society.