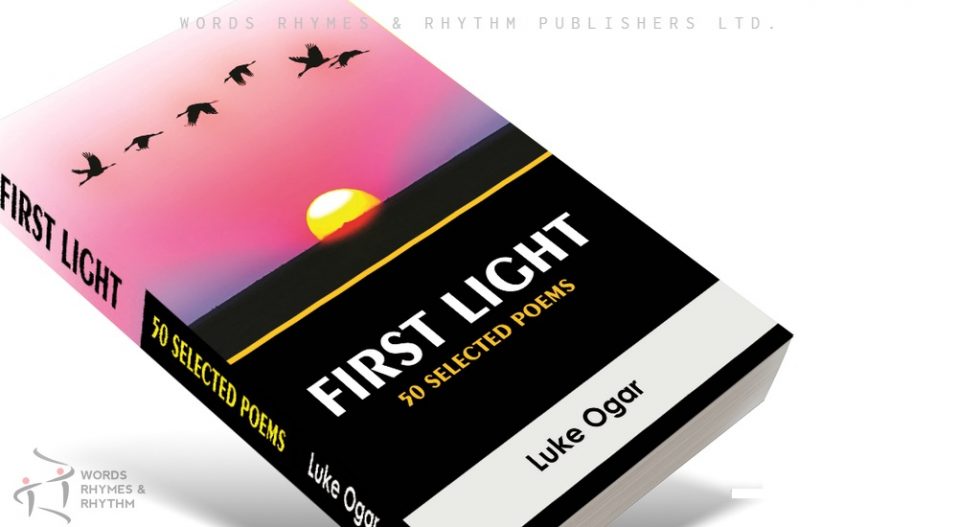

TITLE: FIRST LIGHT: 50 SELECTED POEMS

AUTHOR: LUKE OGAR

GENRE: POETRY

PUBLISHER: WORDS RHYMES AND RHYTHMS LTD

YEAR OF PUBLICATION: 2018

ISBN: 978-978-967-585-2

NO. OF PAGES: 70

REVIEWER: EUGENE YAKUBU

First Light is witty and the author should be applauded for his interesting rhyme pattern and its ability to make optimal semantic sense in the sentence or line despite having to choose carefully and painstakingly the words that will both be fitting to the idea being related and at the same time the preceding and succeeding rhyme scheme as the case may be.

The collection is garnished with significantly sublime and graceful expressions which the poet exudes faithfully in every poem and line.

The perceptive lines are as fascinating as the themes he covered. His words are sharp, each able to stand on its own and at the same time contributes in adding meaning to the general ambiance of the poems, the tone, the style and the theme.

His imagination is concise and acute. Every idea, every vision is keenly related. For example, in the poem Shooter, he refers to the marksman ability to shoot with precision and timeliness as “…ready to fire at the littlest speck” (50). He captures the minutest of detail and paints the picture vividly in the reader’s mind like a movie.

In this collection, it isn’t just the poet speaking to himself, he relates details accurately to the reader in succinct lines pregnant with infinite meanings. His ingenuity lies in his ability to say so much in so little lines: a major feature of good poetry.

In this collection, it isn’t just the poet speaking to himself, he relates details accurately to the reader in succinct lines pregnant with infinite meanings. His ingenuity lies in his ability to say so much in so little lines: a major feature of good poetry.

The poet uses a fair dose of archaic English language too, giving the poems a classical feel of Shakespearian English. He meddles with antediluvian words like “nought”, “nay”, “hast”, “nigh” and his ability at employing them adequately is refreshing and mesmerizing.

Ogar takes the word out of place, takes the ideas out of place and also the reader out of his line of thought and by so doing totally reinvents meanings in the poems. He makes familiar things unfamiliar by subtly changing their contexts and meanings, even their grammatical usage and morphology so the reader can see them in a new light and can leave indelible images in his memories.

This technique formalist literary critics calls defamiliarization and see it as that which keeps a reader anticipative and attentive to the art whereby by disrupting the modes of ordinary linguistic discourse, literature “makes strange” the world of everyday perception and renews the reader’s lost capacity for fresh sensation.

In the poem Vigour, we see an intentional bidding to subvert meanings and violating patterns in the sound and syntax of poetic language— including patterns in speech sounds, grammatical constructions, rhythm, rhyme, and stanza— and also in setting up prominent recurrences of key words or images that are still yet semantically correct and the reader has to totally remove himself from the poem and restructure the words on the poem like a puzzle to make sense. Thus, he (the reader) writes the poem as well as the writer.

The poet like conventional poets avoids clarity like a dream. Even though we can read his poem without much effort, we can barely nip his points accurately in the bud, keeping us in that spectral point of elusiveness, of knowing within mystery and decrypting subtle poetical codes and literariness. His ideas are phantasmic and will effortlessly enthrall readers in his superficial world, however, the point they tender seems ungraspable and dreamlike.

Ogar writes in diction and meter modeled on conversational speech, and often organized his poems as an urgent or heated argument with the universe, with himself, an indifferent reader, a reluctant lover, nature or even God. He employs a subtle and often deliberately outrageous logic, realistic, ironic and sometimes cynical in his treatment of the complexity of human motives whether writing poems on the universe, nature, or religion, he is above all witty in making ingenious use of paradox, pun and startling parallels in simile and metaphor and imagery.

The beginning of poems like Harmattan, Blossom, Introitus, and Extreme Nature reveals the sudden tactic, the dramatic form of direct reference, the compelling conversation and the rhythms of the living voices that is being appeased or apostrophized.

The rhythmic poem Hellish Holiday is musical and poetical. The poet brings together resounding rhythms amidst echoing alliteration and assonance. As the reader reads or rather sings through the lines, he feels the words clashing like cymbals and echoing like talking drums.

The poet’s mastery with onomatopoeic word has made him an outstanding poet who should be valued far above the words in his poems but also for his ability to weave beautiful words like a musical lyric. The poet in his witty manner refers to the sun as “chimney churning” and “infernal flames flaring”.

his tremendous use of words and precision of details are adorned with lofty word-play to give poetry variety and limitless artistry. In the same poem he says with a poignant use of alliteration that the sun has “glorious gleams glaring” and is a “blazing ball burning” (55).

The reader should come prepared to be aroused and enthralled in such artistry which the poet promises on.

In Hellish Holiday, the poet reconciles the universe and the cosmic bodies as having a symbiotic relationship with each other which all contributes in making the universe workable and habitable for man. For as the sun shines steadily, it “warms… everything around” and then “shines on both green and rust”, and then melts the ice which causes seasons and times where plants grow and die because the earth which the poet refers to as a “terrestrial ball burning” to give day and night and all these marvelous process is possible because there is a “solar director syncing the rhyme” (God).

The poet’s creativity is superb, his ability to weave ideas with words and successfully tuck a whole geography of the universe in a 28 lines poetry of 7 verse.

The curt titles the poems carry are usually peremptorily revealing and give substantial information on the poems. For example, the title of the poem Clockworks prepares the reader to expect the onomatopoeic sounds and rhythms. The poem begins “Tick tock, tick tock/ A second-hand runs the clock/ Ding dong, ding dong/ Bells will chime in hourly song”. The poet offers more of this interesting sound play in poems like At the Pub where he uses repetition for emphasis making the poem musical.

Worthy of mention is the philosophical and realistic poem Open Square where the poet uses the image of the market square to denote life where different sellers and customers come to trade and finally return to our eternal abode.

Ogar’s imagination is as precise as a pin and what is even more amazing is that he doesn’t employ random words but carefully selected dictions that fit the rhyme scheme, rhythm and the semantic structure— a perfect example of a sophisticated art.

He almost always successfully drives his point home and reconciles his words accurately. His poems are worth reading, and not just for their turgid diction and lofty ideas but for their ability to reinvigorate the reader’s mind and offer him a chance to dust his dormant intellect too.

You must be logged in to post a comment.